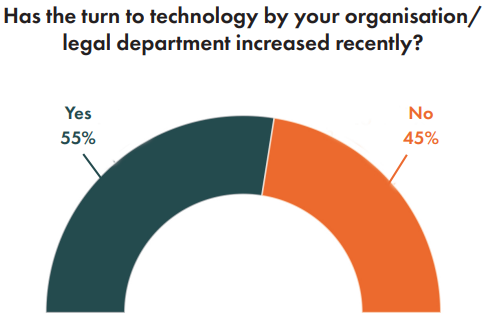

The speed at which technological advancements occur is pressuring legal departments to embrace change. We have asked general counsel if the turn to technology by their organisations has recently increased.

The findings report that 55% of the respondents answered ‘Yes’ to the question, indicating that for all surveyed, in-house legal teams operated under the assumption that recently increasing legal tech was either necessary or a pre-emptive decision. This desire of their companies is guided by basic market forces from without to increase efficiencies and internal pressure from legal teams to alleviate increased pressure on legal teams.

Note that the question was limited to recent increases in implementation of legal tech, therefore the set of respondents to the question that answered ‘No’ may very well have relatively recently introduced legal tech or already be using legal tech. Such a coarse-grained answer does not capture any variance in the beliefs or attitudes of GCs that conducted the survey. However, even with this coarse-grained question, the results indicate that as today’s legal departments continue to evolve in response to corporate demands and become more complex, driven by the introduction of new and more demanding requirements, in-house legal teams appear to think legal tech is the best option to respond to such a challenging environment. This reflects the belief that implementing software and other tools scales up in ways that hiring more in-house counsel and other members of legal teams cannot.

One possible inference that can be drawn from the data is that within this 45% that affirm there has been no recent increase in legal tech, there is a subset of this group that belong to organisations that have not been concerned with implementing legal tech. In these cases, part of the reason is likely found in the limited budget and conflicting priorities within corporations. This subset of GCs may want or even need new forms of legal tech to alleviate increased workload; however, due to internal tensions within a company, they may be unable to secure the necessary tech.

Additionally, in some cases, it cannot be ruled out that an increased market of legal tech produces a paradox of choice: there may be too many options available on the market at this point, cognitively overwhelming legal teams and GCs who wish to implement legal tech that would be right for them, but feeling stressed and incapable of making appropriate decisions without a clear preference for an option that appears superior to other options.

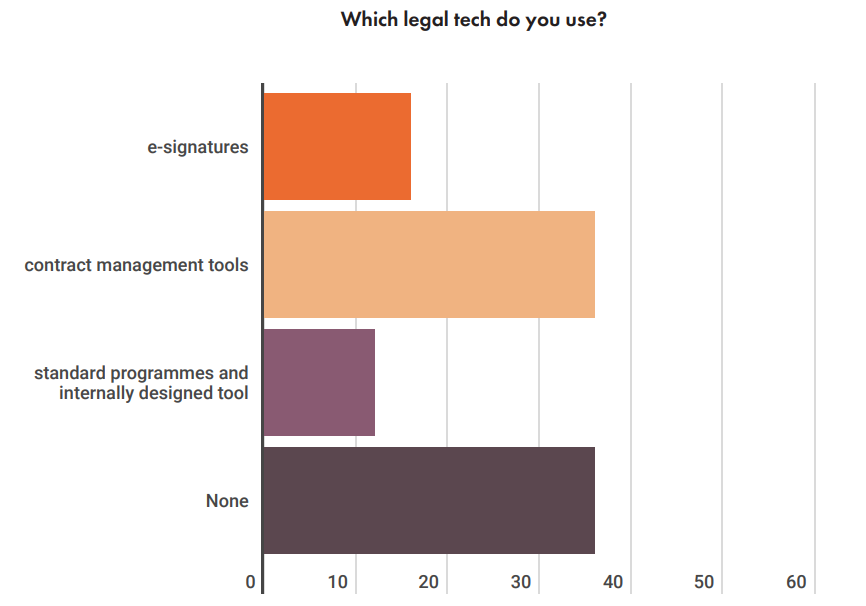

Results show that more than 64% of the respondents adopted legal tech to carry out daily tasks. When taken alongside the previous question, we see that at least 11% of respondents that answered ‘No’ to the question of whether they have implemented new legal tech recently already have some form of legal tech in place. This gives a more accurate picture where things currently stand, with 36% of all GCs surveyed currently not implementing legal tech.

Of this 36% that did not implement legal tech, their responses are illuminating. In the opinion of some respondents, their decision to not implement legal tech was due not to any decision made by in-house teams, but due to external corporate pressure. A common reason behind the rejection of technology seems to be budgetary constraints, defined by one general counsel as ‘too expensive to be used for in-house tasks’, an argument sustained by another counsel who supports that before making such investment, the department must assess the value that legal tech brings to the team.

Of note, no respondents gave any indication that they were purposefully avoiding implementing legal tech out of any concerns about its effectiveness or operating under the assumption that legal tech was a fad; rather, one illustrative response helps clarify how little funding in-house legal teams receive: as GC notes, ‘we only use free access databases. Other tools seem too expensive for their use on an in-house team’, providing a clearer picture of the corporate environment in-house legal teams find themselves in.

Between the set that do implement legal tech, however, over 36% use contract management, review, and research tools. Over 16% of the respondents use e-signatures software, and the remaining 12% use more standard programmes such as the Office package and internally designed tools. A common maxim in corporate procurement is ‘fast, cheap, good. Pick two’. If you’ve ever gone through a procurement process you know that sometimes you will only have one option. We can see this in play with the types of legal tech that have been implemented, ranging from bespoke, customised legal tools or highly complex AI-based tools to household names, such as Word or Adobe. Bespoke legal tech will likely be good, but it won’t come cheap, and procurement may not even be fast; however, off the shelf corporate software may be fast and cheap, but it may not get anywhere close to bespoke software in dealing with the needs of in-house legal teams.

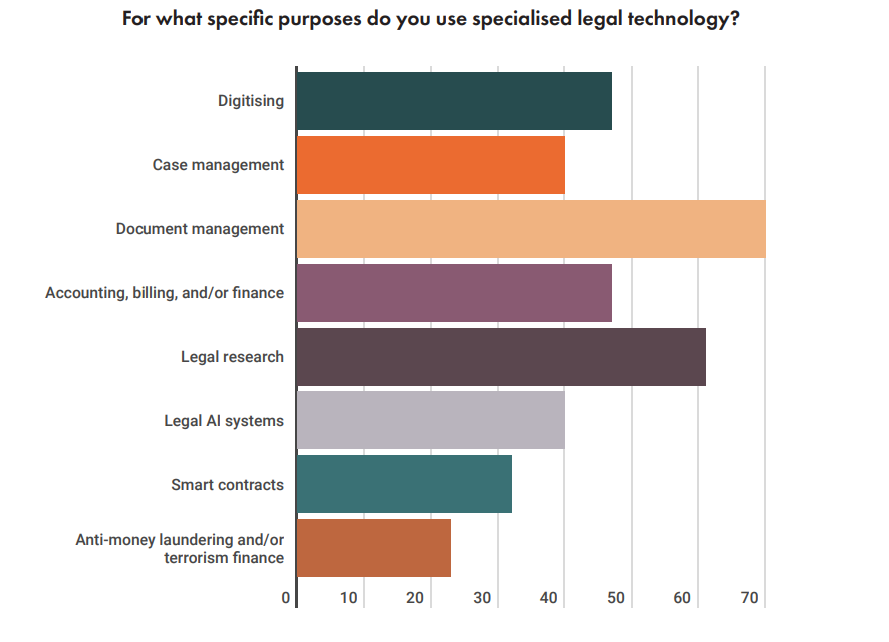

A follow-up question addressed the broad range of purposes of legal tech used by in-house counsel. The majority of respondents noted they used legal tech for document management (70%) and legal research (61%), followed by accounting, billing, and or/ finance (47%), case management (40%) and legal AI systems (40%). We determined that a majority of respondents who employed legal tech used legal tech for at least two purposes, with, surprisingly enough, a small cohort only using legal tech for either document management (4%) or legal research (9%), while a large minority (41%) of respondents used at least four different purposes. Surprisingly, 6% answered that they used legal tech for all recorded purposes.

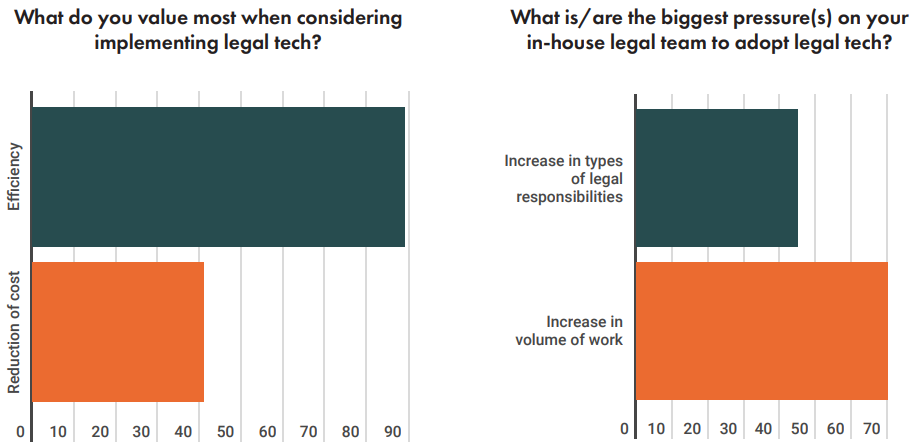

We also asked respondents about what did they value most when considering implementing legal tech. Unsurprisingly, when given a choice to list their priorities, 89% responded that they valued efficiency. This overlapped considerably with respondents who also prioritised reduction of costs, with only 5% of respondents choosing only the value of reduction of costs and no value for increased efficiency. Notably, only one respondent that chose ‘other’ identified a third value that they prioritised over efficiency and reduction of costs, specifically compliance.

A further question we asked related to the increased pressures on in-house counsel driving the adoption of legal tech. The results matched the expected outcome, with 70% of respondents noting their biggest pressure was an increase in volume of work, followed by 45% seeing an increase in their legal responsibilities. Of particular interest was the fact that a full 35% of respondents only answered their biggest pressure was an increase in volume of work; 32% selected both an increase in types of work and volume of work; and only 14% responded solely that their biggest pressure was an increase in types of work, not volume. A statistically insignificant cohort responded that their biggest pressure was neither of the two main options, but rather due to an increase in regulations (2%) or pressure to integrate into a broader team (1%).

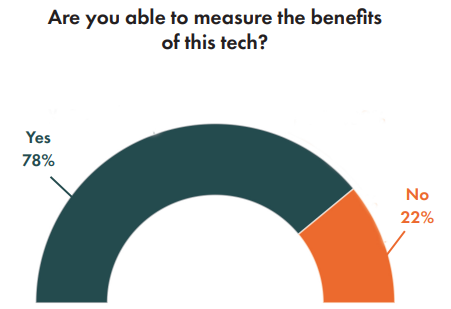

Understanding and measuring the benefits of legal tech is not as easy as it may seem. We have asked our respondents if they can measure the value this technology brings to their jobs. Surprisingly, we had a precise 50-50 ratio.

However, further analysis shows that this 50-50 split in the result is an artefact of the survey, since all respondents that explained they did not use legal tech also answered ‘No’ to whether they were able to measure the benefits of legal tech. This means 36% of respondents must be excluded from this survey question as their null answers skewed the results. A more accurate breakdown of the data revealed that a full 78% of respondents who did implement data tech were able to measure the benefits of legal tech, results that were as surprising as the initial results, primarily because it illustrates how for a majority of in-house teams, legal tech is thankfully subject to Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), were there to be any auditing or examination of the effectiveness of a particular implementation of a type of legal tech.

Additionally, after reviewing qualitative feedback from GCs that did answer affirmatively, this is a group of GCs that are highly enthusiastic about legal tech, as well as excited to detail the ways legal tech has helped their teams. The reasons vary from timesaving to transparency, efficiency and uniformity, and higher productivity.

Some of the GCs offer a different perspective when assessing the value that legal tech brings to their department. They frequently talk about saving time on routine tasks. One GC even said, ‘we’ve had 15% time saved overall’. Another notes, ‘we’ve had time saves, less errors, and more uniformity’. A third GC says, ‘we’ve had lots of time saved through standardisation and cost-reduction in hours spent per contract’.

Even for GCs that have implemented less extensive forms of legal tech such as e-signatures and don’t have tools in place to measure effectiveness express a sense that legal tech has saved them time: ‘it’s just a gut feeling I have that e-signing is faster than the traditional way’.

And for GCs that can’t yet measure the benefits of legal tech in the short-term note that they are still in early stages of implementing new tech. These changes will only be measurable in the medium-to-long-term. Nevertheless, even if there are no measurable metrics in place, lawyers still cannot praising legal tech. As one in-house lawyer affirms, ‘I can’t live without it’.